Farmers Use Fit Bit Style Technology to Monitor Cow Health

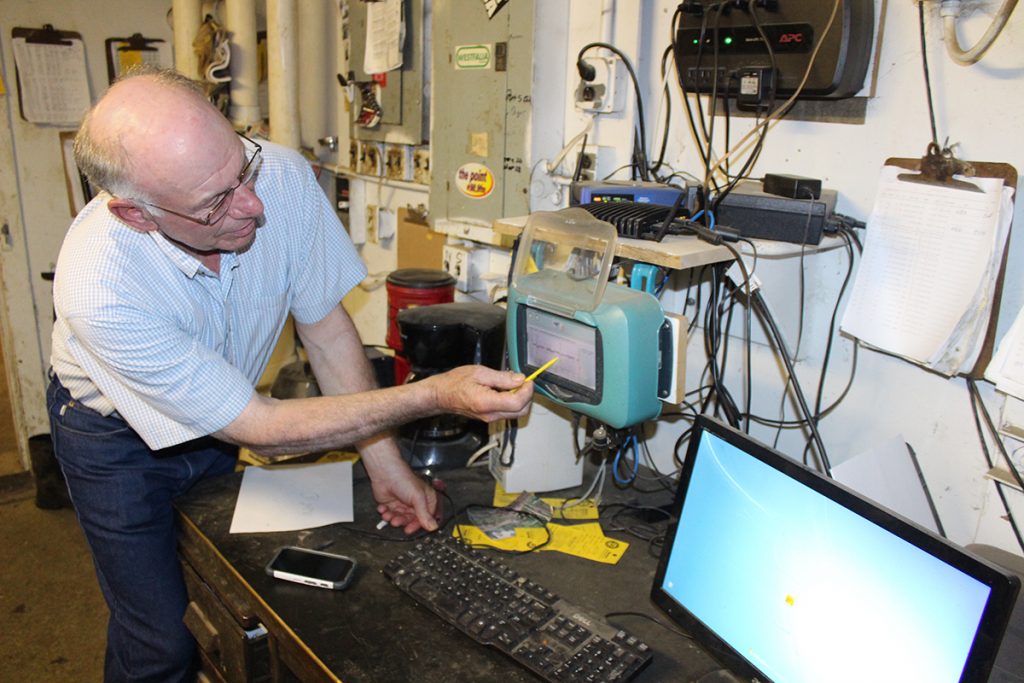

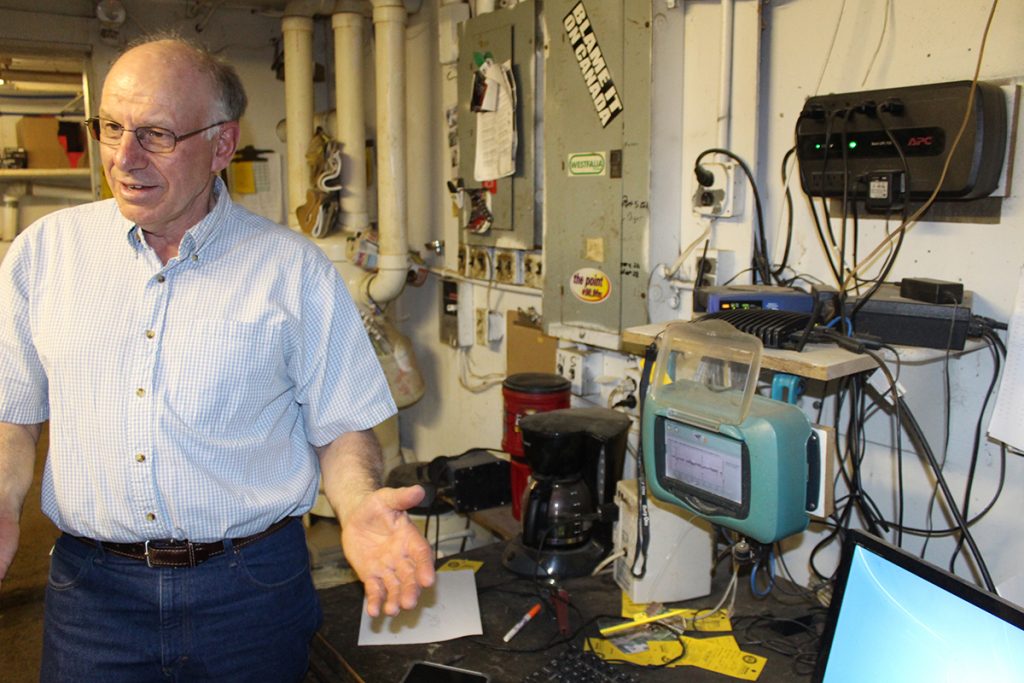

A farmer can see how many times a cow chews cud, if milk production stays at the same rate, and how much she moves around. These are all health indicators that help farmers to be more proactive in dealing with possible health issues. If a cow’s numbers are off from the normal range, the dairy farmer is alerted.

In order to do that, she must swallow, then regurgitate her food. Chewing it over and over so that it is broken down enough to be digested. If a cow is not chewing cud, it’s a red flag that something is wrong and she’s not feeling well.

People spend a lot of time and money researching dairy cows. Dairy farmers use that information to make sure their cows are as healthy and happy as possible. Someone even took the time to count how many times a cow chews the cud, which is about 30,000 times a day.

Research shows how much a cow should move around on a daily basis. If she’s not moving enough, it might mean she is sick, has a sore hoof, and should be checked. If she’s really active and moving around, she’s probably in heat and ready to be bred.

Before this technology, farmers relied on their own observations and guesswork. Now, they can catch a problem much earlier. If a cow is showing signs that she’s sick, catching it earlier means she can be taken care of before a problem gets more serious. Often, fewer drugs and antibiotics are needed. Farmers and veterinarians use the data to tell if a cow is responding to treatment sooner rather than waiting to see if one thing works before trying another.

This ensures they get enough without overeating and making themselves sick. It can also help to wean them. It cuts back on milk as they eat more hay and grain. Calf feeders like this are used in group housing rather than bottles and buckets when calves are housed individually.

Calves and robotic feeders use similar Fit Bit style technology. Many dairy farms, like Lilley Farms, use group housing for their calves. Making sure each calf gets enough to eat and not too much would be difficult to do without the feeders.

The calves aren’t fed twice a day on a schedule. They can choose to drink milk when they want, but they can’t have as much as they always want. Too much milk can cause them to have scours or diarrhea.

A button on their ear tells the computer that runs the feeder which calves can have more milk and which ones have had their fill for the day. As calves get older, the amount of milk they drink every day is cut back as they are weaned. Then, their diet consists more of hay and grain.